Hi everyone! I’m officially settled into my little bachelor pad right on the water, just four minutes away from Picton Animal Hospital (thanks Kijiji)! Picton is a quaint little tourist town in Prince Edward County (wine country!) about thirty minutes South of Belleville, or an hour and a half East of Toronto. (Here's a photo on the dock at Picton harbout.)

First Impressions

I think the biggest adjustment so far has been seeing the difference between the straightforward, textbook cases we see in the classroom and real patients. Sometimes, even when you do all the appropriate tests, you don’t come up with a clear-cut diagnosis. Real patients don’t always read the textbook.

I learned very quickly that Prince Edward County is a hotspot for Lyme disease (a bacterial infection carried by ticks). In my first week, we diagnosed 7 new cases, and many of our patients coming in for routine visits had tested positive for Lyme in previous years and are still carrying the disease today. “Most” dogs do not get sick from this disease, but in a geographic region where Lyme disease is rampant, PAH sees clinical cases (dogs that are visibly affected) on an almost daily basis.

On the large animal side, I got to watch my very first bovine surgery; a right-displaced abomasum (twisted stomach) correction. I have also palpated three times as many cows now as I had when I left OVC at the end of April. Rectal palpation is an important part of bovine and equine veterinary care, because you can assess the locations and health of various organs (such as that twisted stomach!), as well as identifying whether an animal is ready to be bred, already pregnant, and how far along she is. I was able to palpate both dairy and beef cows this week, and was pleasantly surprised by how docile the beef cows were!

Triaditis

Triaditis is a syndrome in cats with which I was not very familiar prior to arriving at PAH; but after seeing three to four suspected cases within my first three days, it was obvious that I needed to do some research. Triaditis is exactly what it sounds like; a triad (3) of “itis” (inflammatory conditions). The three disease processes involved are inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the small intestine, pancreatitis, and cholangitis (a disease of the liver/gall bladder). Triaditis is typically a condition of older cats.

Triaditis is a syndrome in cats with which I was not very familiar prior to arriving at PAH; but after seeing three to four suspected cases within my first three days, it was obvious that I needed to do some research. Triaditis is exactly what it sounds like; a triad (3) of “itis” (inflammatory conditions). The three disease processes involved are inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) of the small intestine, pancreatitis, and cholangitis (a disease of the liver/gall bladder). Triaditis is typically a condition of older cats.

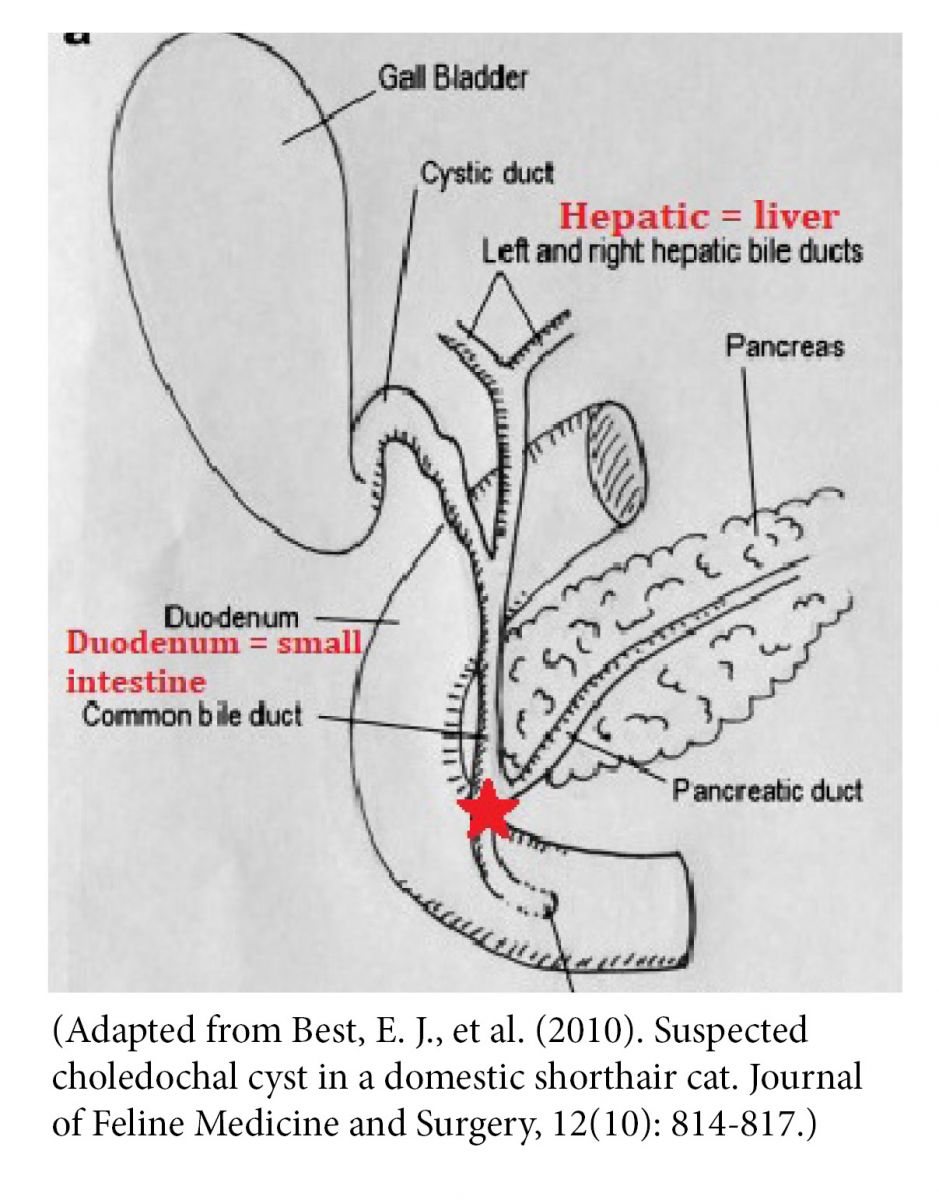

Triaditis occurs in cats because of their GI anatomy: there is one main duct entrance (red star) to the small intestine that stems from the liver/gall bladder AND the pancreas. It is possible that disease changes in one of these organs may spread to involve the others as well. In dogs, there are two separate ducts, which is why they aren’t prone to triaditis.

Triaditis usually results in gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and anorexia (not wanting to eat). You may also see lethargy or jaundice. It is difficult to make a definitive diagnosis of triaditis (biopsies are typically required), but we can usually arrive at a presumptive diagnosis with blood work and urinalysis (we look at the urine to make sure these signs are not due to kidney disease, which is also very common in older cats). Abdominal ultrasound is another non-invasive tool we can use to visualize changes in these organs, and give us more confidence in a diagnosis of triaditis.

Triaditis is a chronic disease that typically cannot be cured. We can however manage it quite well, and can still achieve good quality and length of life. There are lots of possible drugs that can be used to control this disease, and the hard part is often finding the combination of medications that works for each animal. In the beginning, we often try to get control of the disease using antibiotics, anti-nausea medication, anti-inflammatories, and fluids (vomiting and diarrhea can lead to dehydration). Long-term treatment options can include immunosuppressive therapy (triaditis, like IBD, may have an auto-immune component), diet, antioxidants, and liver-protective drugs.

That’s all for today, thanks for reading! I’m looking forward to seeing what’s to come in the following weeks as I continue to learn more about mixed-animal practice and keep exploring Prince Edward County!