Coming to Australia was a huge gamble. Travelling across the world on my own to a foreign country, subjected to a novel environment with varying mindsets, and with the hope that the placement I chose was as awesome as I imagined it would be. I hoped that I would be able to gain valuable experience at my chosen hospital due to the fact that it was a 24-hour hospital and its close proximity to the University of Queensland School of Veterinary Science. But in all honesty, I really didn’t know. And even so, given my uncertainties, boy did I hit the jackpot! I’ve only been at the Manly Road Veterinary Hospital (MRVH) for a week and I’ve already learned so much. It’s absolutely amazing.

I’m not really sure what I expected. I figured I would spend 8 weeks observing/assisting in a bunch of vaccine appointments, wellness exams, and trying to get comfortable with large animals (because really, they’re scary and I’ll always be a small animal girl at heart).

At MRVH, I’ve been exposed to so many different ailments and diseases. And while the diseases that are native to Australia are interesting, I’m also being exposed to diseases that can and do occur in Canada, but don’t necessarily occur often enough to learn about in a short period of time.

This was amongst the first cases I was exposed to on my very first day. From an expected routine day to a hectic one, this little Staffy received a life saving surgery. Said Staffy presented with a mast cell tumor on the second set of phalanges on the medial aspect of the hind leg (second toe on the hind leg). What some of you may or may not know is that mast cell tumors can be quite serious, and have the tendency to become malignant very suddenly and very quickly. So given this, the client opted for digit amputation to prevent its potential spread. While surgeries like these may not be exceedingly difficult (although still require an experienced veterinary surgeon), it is extremely difficult to excise wide enough margins around the tumor to ensure that no tumor cells are left over that could lead to recurrence. These photos are post surgery when the dog left the hospital happy and healthy!

Later that week, the hospital received a referral orthopedic patellar luxation repair. Although I’ve learned about it in school, I learn a lot more efficiently and effectively through hands on learning. So this case was great for learning about and practicing how to diagnose a luxated patella (when the kneecap dislocates or moves from its normal location). As I am demonstrating in this video, feel for the trochlear groove (where the patella sits), and slowly move your finger side to side. The notch/jump that you can see in the video shouldn’t happen in a normal animal and is thus characteristic of a patellar luxation.

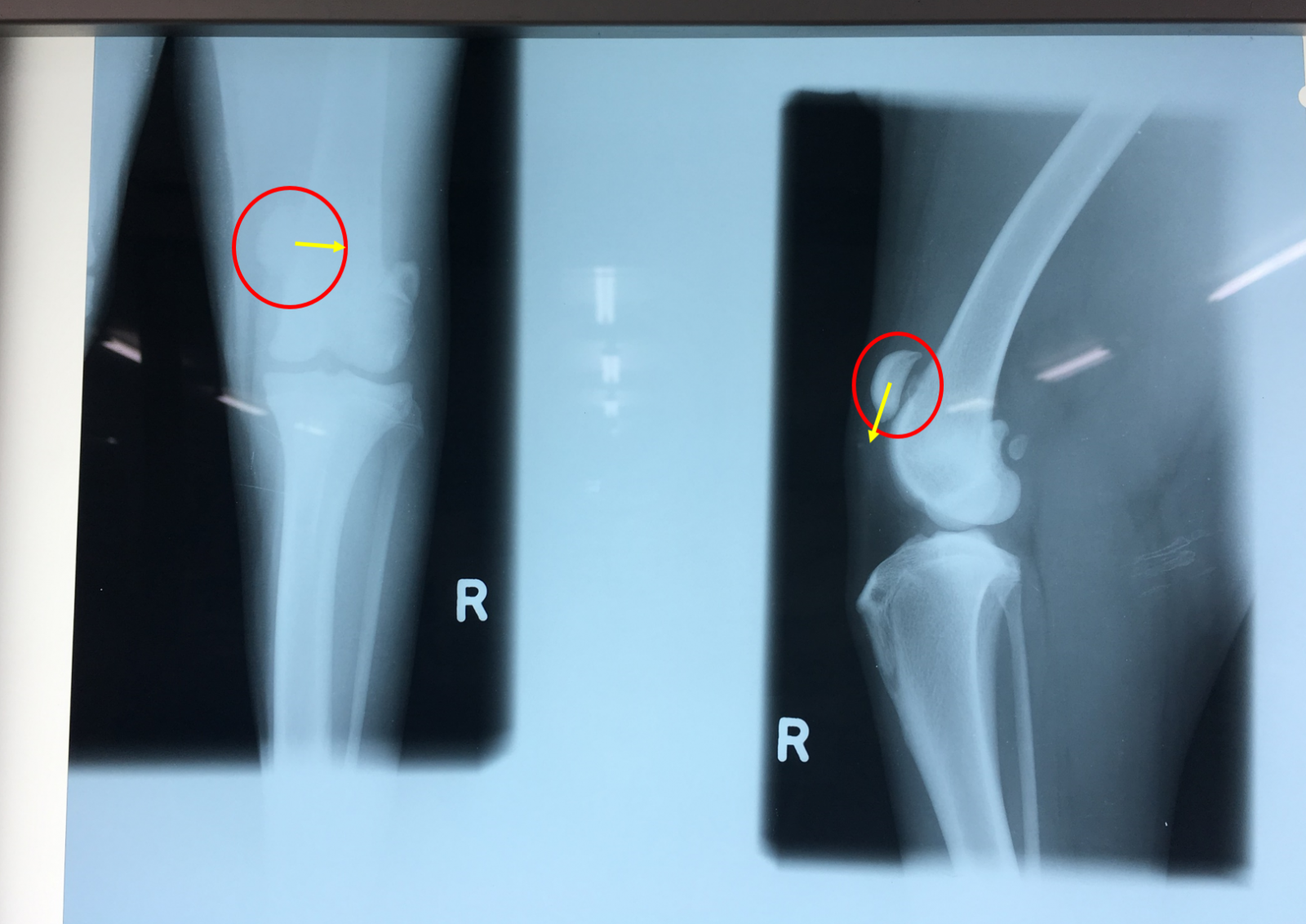

Here is what it looks like on radiograph. This dog in particular has a right patellar luxation, which usually means that the patella is displaced medially (towards the middle). This dog had the added bonus of having a congenital proximally displaced patella which predisposed it to the current patellar luxation that caused the onset of its presenting lameness. Circled in red is the patella on two separate views, and the yellow arrow indicates where the patella should be in a normal dog.

You know how whenever you go to the vet, the vet encourages tick prevention for your animals? Because our tick preventative medications and compliance with administration are relatively good in Canada, we hardly ever see cases of tick paralysis. Tick paralysis is an ascending paralysis that starts in the hind legs and progresses cranially (toward the head) no matter where on the animal the tick was found. It is an especially unfortunate disease because the animal is paralyzed but is completely aware of its surroundings. Tick paralysis in Canada is caused by the American dog tick (or Dermacentor variabilis for us nerds out there). In Australia, it is caused by a tick known as Ixodes holocyclus, and is actually quite prevalent. It has declined over the past few years through the use of preventatives, but is still quite common on the east coast of Australia as it prefers humid climates. Treatment involves an intensive course of supportive therapy with the administration of tick anti-toxin serum, as well as manual tick searches via full body shaving. The animal is kept in a quiet environment and handled as little as possible to decrease the number of stressors; as stress - especially in cats - can cause an increase in oxygen requirement, and can ultimately lead to respiratory failure. Veterinarians also need to be careful with fluid administration in cats, as tick paralysis causes a fluid shift so that even if the lungs appear to be clear on radiographs, subsequent fluid administration can still lead to a fluid shift which can cascade into non cardiogenic pulmonary edema. I was fortunate (although unfortunate for the animals) to see two cases this week, one in a cat, and another in a kid (baby goat).

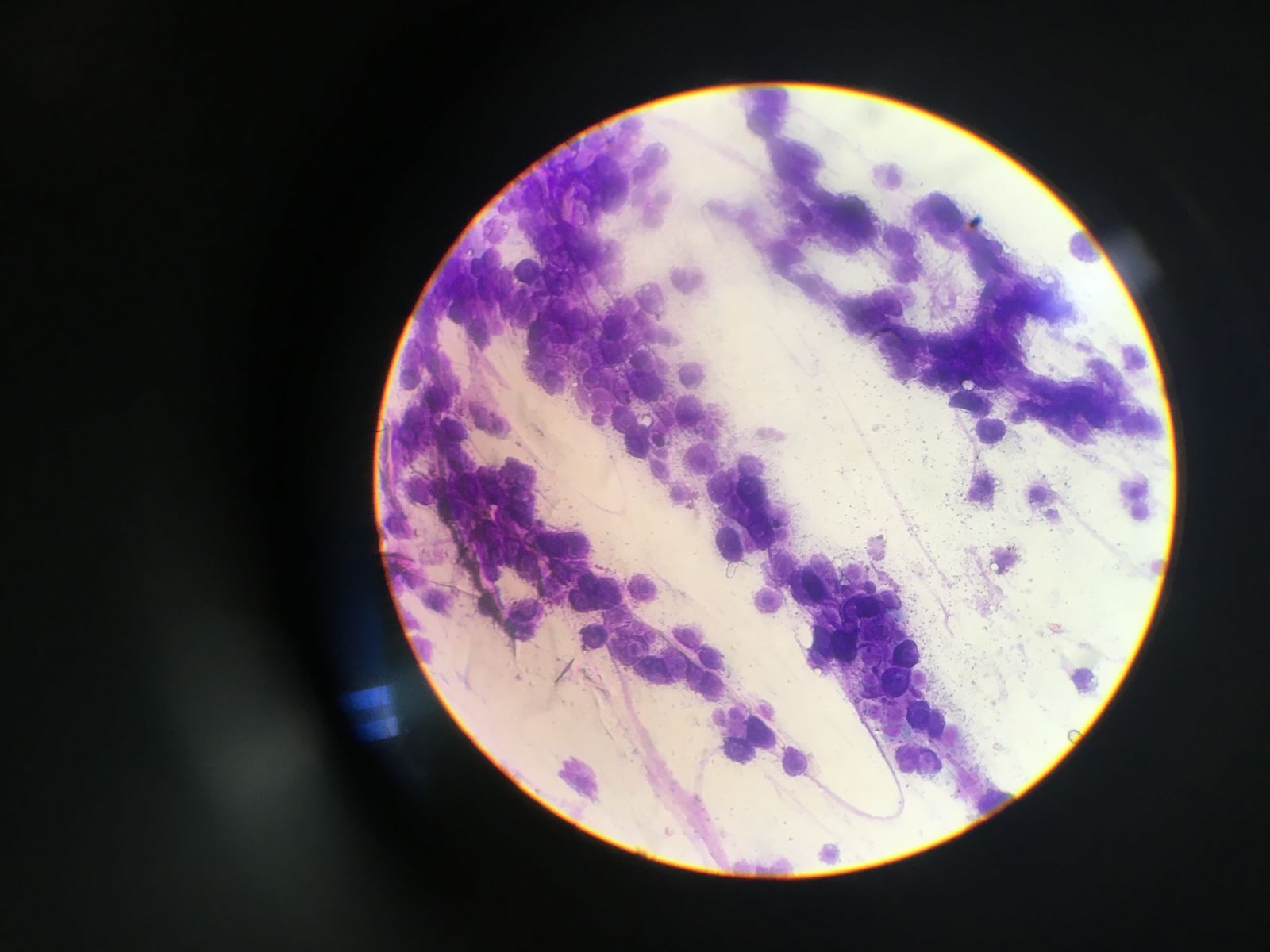

Sometimes in the world of veterinary medicine, animals will get diseases and ailments that we’d love to know the particular cause of, but unfortunately we can’t especially if the client opts to not send samples for pathology (which is completely fair, it can be quite expensive). So on one such occasion, we performed a cosmetic removal of a lump on the hind leg of a dog as the owners were worried that it might become malignant, even if we didn’t have the diagnostics to support it. Luckily, MRVH has a diagnostic lab, where a vet student like myself can practice doing a fine needle aspirate and cytology on an “unneeded sample” (unneeded as the clients opted out of diagnostic pathology). And this is what I found:

To a student like me, I see a lot of cells with varying sizes and varying nuclear:cytoplasmic ratios (the ratio of the size of the nucleus of the cell to the size of the cytoplasm of the cell). Definitely not normal, and somewhat matching a textbook description/photo of a squamous cell carcinoma, but who knows. Only a veterinary pathologist could really tell for sure. Good thing the clients opted for this lump to be removed!

In addition to all this, being exposed to two separate GDV (gastric dilation volvulus) cases (their fourth in the last month), pancreatitis, dog bite attacks, a bunch of wildlife injuries, dentals, desexing, and more, I believe I can say that week one was a success!

And after a long hard day’s work, it’s time to enjoy the sights along the beautiful Brisbane River.

Well, here’s hoping you enjoyed this week’s blog. Stay tuned for the next segment of “Adventures of (future Dr.) Ari in Aussie!”