Growing up, I’m sure we’ve all heard the expression “it’s what’s on the inside that counts”. Well, veterinary medicine takes this phrase to a whole new level when it comes to diagnostic imaging. With advanced imaging modalities such as CT scans and MRI, we can get a very detailed picture of pretty much any organ or tissue inside an animal. While radiology (X-rays) is probably the most common imaging technique used in general practice, there are some disease processes that require more advanced methods to make a diagnosis.

Learning how to interpret radiographs is hard enough, so I was definitely in for a surprise when I found out that my clinic commonly uses ultrasound and CT scans in addition to radiographs. One of the first interesting ultrasound cases I saw came a few weeks into my externship, when a mixed breed dog presented with weakness, abdominal distension and pale mucous membranes (gums). Pale mucous membranes are often a sign that the animal is experiencing blood loss or anemia. Due to the abdominal distension, the vets began with a thorough ultrasound scan of the abdomen. The first thing we noticed was a moderate amount of free fluid in the abdominal cavity. Upon further scanning, the vet found the probable cause of the dog’s problems – a large mass (tumour) was evident in the dog’s spleen. A sample was taken of the fluid in the dog’s abdomen, which revealed fresh blood. The accumulation of blood in the abdominal cavity is called a hemoabdomen.

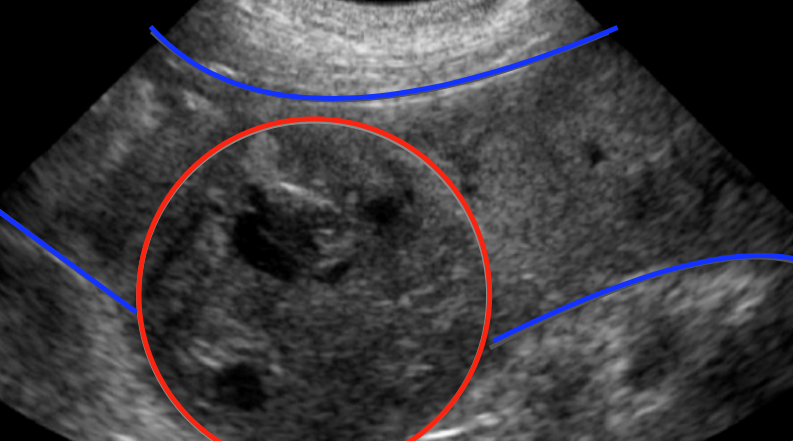

With all of these findings together, the vets suspected that this dog had a splenic hemangiosarcoma, which means that it has a cancerous tumour of the blood vessels in the spleen. These tumours can often bleed and rupture, leading to a hemoabdomen. Depending on the amount of bleeding, this can be a very severe emergency that can lead to death. This tumour is also highly metastatic, which  means it can spread easily to other organs. This dog first had chest radiographs performed, which luckily showed there was no evidence that the cancer had spread to the lungs. With no evidence of metastasis, the primary method of treatment is a splenectomy, which means removal of the spleen. Chemotherapy is also recommended following surgery. Unfortunately, the prognosis is not very good with this type of cancer, however removal of the spleen with chemotherapy often gives patients an extra four to six months of life. The dog in this case ended up going for a splenectomy the next day and started on chemotherapy shortly after. Hopefully she is enjoying as much time as she can with her owners now! (Figure above on the right shows an ultrasound image of a splenic mass. The normal spleen borders are outlined in blue and the mass is outlined in red.)

means it can spread easily to other organs. This dog first had chest radiographs performed, which luckily showed there was no evidence that the cancer had spread to the lungs. With no evidence of metastasis, the primary method of treatment is a splenectomy, which means removal of the spleen. Chemotherapy is also recommended following surgery. Unfortunately, the prognosis is not very good with this type of cancer, however removal of the spleen with chemotherapy often gives patients an extra four to six months of life. The dog in this case ended up going for a splenectomy the next day and started on chemotherapy shortly after. Hopefully she is enjoying as much time as she can with her owners now! (Figure above on the right shows an ultrasound image of a splenic mass. The normal spleen borders are outlined in blue and the mass is outlined in red.)

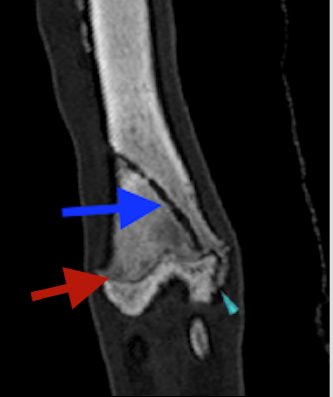

Another really cool diagnostic imaging case I got to be involved in was a CT scan on a dog with a broken leg. The dog in question, a one-year-old Maremma, presented to our clinic after his play time with another dog got a little too rough and he began limping on his right hind leg. Radiographs of his leg revealed a fracture of the right tibia, or shin bone. One concern with fractures in young animals is whether or not the fracture affects the physis (growth plate), the area at the end of long bones where new bone forms. A fracture involving the physis can lead to decreased bone growth and asymmetry in bone length. For the dog in this case, it wasn’t 100 per cent clear on radiographs if the fracture crossed the growth plate or not. The vet recommended a CT scan for this dog, as it provides more detailed images of bones.

To perform a CT scan, animals are first placed under general anesthesia to ensure they keep completely still during the scan. You can’t just tell animals to stay still and hope they listen! Most veterinary clinics do not have a CT scanner on site, so the animal is usually taken to a specialty hospital or referral clinic that has the appropriate equipment. The scan itself is remarkably quick, only taking about thirty seconds to produce detailed images of the animal’s body. CT scans work by obtaining image “slices” of a patient, which are later reconstructed into 3D models of the affected area. In 2D images that are generated on radiographs, bones and other tissues can overlap each other, which can make it hard to evaluate each individual structure. The generation of detailed 3D images is one reason why CT scans can provide better diagnostic quality over radiographs. (Here’s a brief video on CT scans in animals.)

To perform a CT scan, animals are first placed under general anesthesia to ensure they keep completely still during the scan. You can’t just tell animals to stay still and hope they listen! Most veterinary clinics do not have a CT scanner on site, so the animal is usually taken to a specialty hospital or referral clinic that has the appropriate equipment. The scan itself is remarkably quick, only taking about thirty seconds to produce detailed images of the animal’s body. CT scans work by obtaining image “slices” of a patient, which are later reconstructed into 3D models of the affected area. In 2D images that are generated on radiographs, bones and other tissues can overlap each other, which can make it hard to evaluate each individual structure. The generation of detailed 3D images is one reason why CT scans can provide better diagnostic quality over radiographs. (Here’s a brief video on CT scans in animals.)

This dog’s CT scan went well and he recovered from anesthesia without any complications. The CT images revealed that the fracture did indeed involve the physis. However, since the dog was already one year old, it had likely finished most of its growing by this point, which definitely worked in the dog’s favour. If the dog still had a lot of growing to do, this fracture could have caused much more serious problems. The CT scan was very useful in this case to determine the extent of involvement of the growth plate and to predict the prognosis for fracture healing. This dog’s fracture was treated with a Robert-Jones bandage, a type of external splint applied to a broken limb to help stabilize it during healing. (Figure above on the left: An image of this dog’s tibia from the CT scan. The dark blue arrow indicates the fracture, the red arrow shows the growth plate, and the light blue arrow shows the fracture extending beyond the growth plate.)

Although it can be tough to interpret these tests, they are extremely useful in figuring out what’s wrong with our furry friends. I hope you learned a few things from this blog about the amazing diagnostic imaging techniques that we are lucky to have in veterinary medicine!