A middle-aged small breed dog is rushed to the veterinary clinic unable to breathe with mucous pouring from his nose. When he arrives, the vet discovers that the dog also has a high fever, has been vomiting for the last 24 hours, and has lost ten pounds in the last six months. Across town at the local hospital, a sixty year old man is handed a diagnosis of terminal lung cancer. Six months to live. Heartbroken, he returns home to his wife and delivers the bad news.

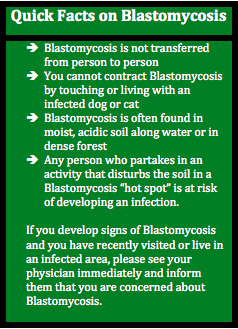

A week ago, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you the connection between these two cases. But after just one week up here on Manitoulin Island, I can tell you that the answer is devastatingly simple. Blastomycosis (“Blasto”) is a fungus found in the soil in certain areas of North America and causes a serious, sometimes fatal, pneumonia in both people and animals. Often misdiagnosed as lung cancer, this deadly fungus has already claimed the lives to two women on the Island in the last year. It is transmitted by inhaling the fungal spores from the soil or through contact with an open wound. In Southern Ontario, a veterinarian or doctor might see a case of Blasto once every three or four years. In the last five days here on the Island, I have seen 6 cases, two confirmed and four pending testing results. It is biological warfare in its most basic form – medicine against an invisible, deadly enemy lurking in the soil all arou nd us.

nd us.

But let’s back up a little bit.

When a dog comes in the veterinary clinic with difficulty breathing, lack of energy and weight loss, there are numerous thoughts that go through our minds as veterinarians. Since we can’t ask our patients where it hurts, we rely on our physical examination of the animal and the information that the owner can tell us in order to create a list of possibilities, known as “differential diagnoses”. We then use a series of tests or diagnostics to narrow down the possibilities, which hopefully leads us to the right answer. For the dogs that present with the signs listed above there are a few differentials on our list: pneumonia, heart problems, upper airway infections, infectious disease, cancer etc. Blastomycosis is usually pretty far down on the list, unless you are in an endemic area or “hotspot” - which, unfortunately for Scott Veterinary Services, we are. In that case, Blasto quickly jumps to the top of the list. Dogs infected with Blastomycosis can also show signs of joint pain, fever, eye infections and non healing skin wounds.

In order to help us narrow down our list of differentials, often our first course of action will be to draw blood and take a set of chest x-rays. There are some specific changes on the blood work that cause us to be more concerned about a Blastomycosis infection but we are also able to rule out other possible diagnoses further down on the list in the process. A set of chest x-rays for a badly infected dog will show round, distinct masses all over the lungs. At this point, we would be pretty much down to two differentials – cancer or Blasto. If there is a skin wound or a swollen lymph node, we are sometimes able to confirm the diagnosis by identifying the fungal spores on a microscopic sample. But the most accurate way to confirm our diagnosis is to send a urine sample to the University of Guelph, who sends it to a lab in Indianapolis - the only lab in North America that is able to test for the fungus. This lab runs the urine test, and then sends the results back to Guelph, who then sends them back up to the Island to us.

Often we begin treatment for Blastomycosis with a powerful antifungal medication before getting these results back, due to the amount of time that it takes to get the results and the serious nature of the disease. We also treat for a bacterial pneumonia with antibiotics at the same time, just in case our diagnosis is wrong. Lastly, we often put our Blasto patients on an antiinflammatory drug to help control the body’s reaction to the dying fungal spores. Usually, a patient gets worse before they get better and even with treatment, about 30% of patients never recover.

Often we begin treatment for Blastomycosis with a powerful antifungal medication before getting these results back, due to the amount of time that it takes to get the results and the serious nature of the disease. We also treat for a bacterial pneumonia with antibiotics at the same time, just in case our diagnosis is wrong. Lastly, we often put our Blasto patients on an antiinflammatory drug to help control the body’s reaction to the dying fungal spores. Usually, a patient gets worse before they get better and even with treatment, about 30% of patients never recover.

Humans show very similar signs, but are often misdiagnosed due to the fact that it is relatively rare. Less than 50% of people infected with Blastomycosis will go on to develop signs of disease, and those signs can be vague and nondescript - weakness, lack of energy, joint pain, flu like symptoms and a chronic cough. Health practitioners up here on the Island are becoming increasingly more aware of the dangers that this fungus poses to the people and a recent community meeting with the Sudbury Public Health Unit was held in conjuncture with the two veterinary clinics in order to pool our knowledge to combat this disease.

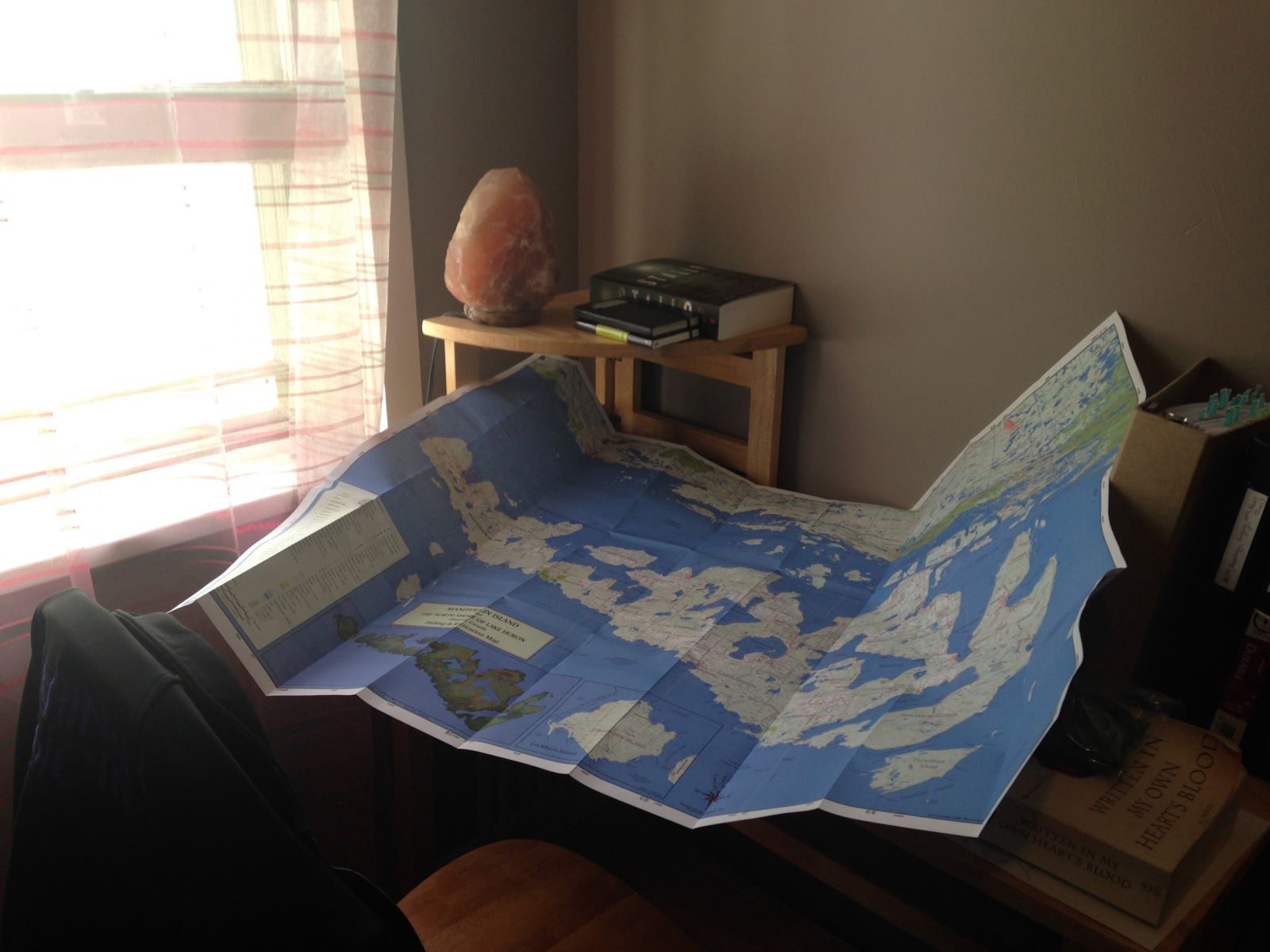

At Scott Veterinary Services, we are plotting the confirmed and suspected cases on a map to help determine the spread of this disease on the Island. While Blastomycosis is not currently a reportable disease, meaning that we are not required to document the location of cases and submit the information to the Ontario government, by treating it as if it were reportable we are better able to provide accurate and informed information to our clients. There is currently no method of isolating the fungus from the soil, so documentation of confirmed cases is the only way to find out the extent of the outbreak.

Occasionally the worlds of human and veterinary medicine collide, and we are able to combine our knowledge to help both people and animals in a method known as “One Health”. Despite the differences between these two branches of medicine, we are stronger when we work together and this concept has been whole-heartedly embraced by the medical professionals on the Island. By sharing our case data and working together to develop treatment protocols, we are hopeful that Blastomycosis will soon become an important differential for any health professional working in North Western Ontario, regardless of the species that they work on.

Occasionally the worlds of human and veterinary medicine collide, and we are able to combine our knowledge to help both people and animals in a method known as “One Health”. Despite the differences between these two branches of medicine, we are stronger when we work together and this concept has been whole-heartedly embraced by the medical professionals on the Island. By sharing our case data and working together to develop treatment protocols, we are hopeful that Blastomycosis will soon become an important differential for any health professional working in North Western Ontario, regardless of the species that they work on.

In the meantime, we continue to fight the biological warfare on the front lines with everything we have – antifungals, antiinflammatories, antibiotics and faith.

Minawaa giga-waabamin, until next week,

Rachael